“Eat your carrots—they’ll help you see in the dark” is a refrain that many of us have grown up hearing at the dinner table, but was it a ruse to get us to eat an affordable, British-grown vegetable?

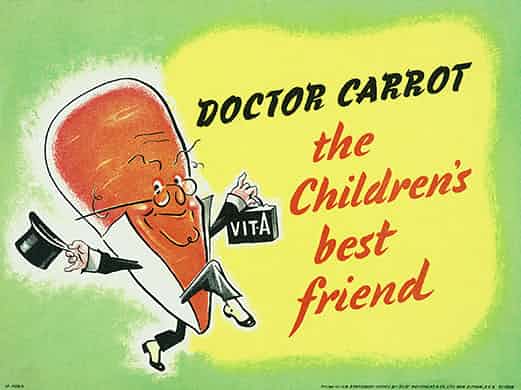

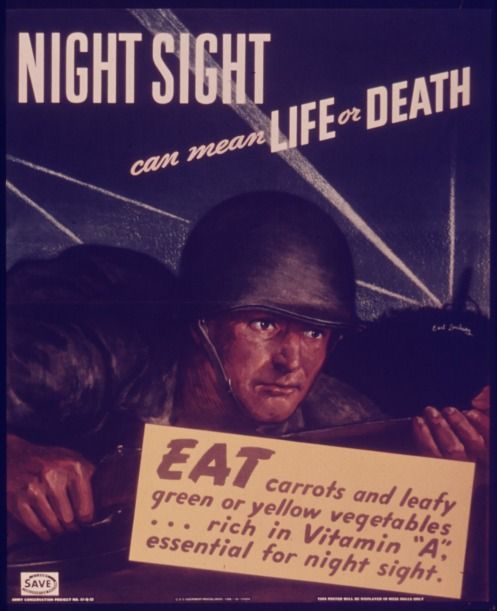

In World War II, the British government appeared to believe in these vision-enhancing properties, as the British Royal Air Force circulated propaganda suggesting that their pilots had excellent night vision because they consumed large quantities of carrots. Dr Carrot, the “children’s best friend” and the “adviser of grown-ups” was co-opted to promote carrot eating to help people see during the blackouts.

But if you ate spadefuls of carrots growing up and still had poor eyesight or had trouble seeing at night, you might have questioned your parents’ folk wisdom. So let’s dig into this a bit deeper to see how much truth there is in the old saying.

Carotenoids, retinoids and genes

Carrots are a good source of beta-carotene, which is one of the carotenoids found in red, orange and yellow vegetables and fruits, as well as in some algae, bacteria and fungi. Carotenoids are precursor to vitamin A, which is essential for maintaining healthy vision. In fact, a deficiency in this vitamin can indeed lead to night blindness. Vitamin A is also one of the nutrients that are important for keeping your eyes lubricated.

Once the body has enough vitamin A for optimal functioning, consuming additional amounts won’t further enhance vision. But when it comes to “optimal”, for many people, carrots don’t cut it. This is because, after they have been absorbed through the gut, beta carotene and other carotenoids have to be converted to retinoids before the body can use them as vitamin A. What enables this conversion is an enzyme called beta-carotene oxygenase 1 (BCO1), and how much of this enzyme your cells produce is determined by your BCO1 gene. Some people have one or more variations (called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs – pronounced “snips”) on their BCO1 gene that makes them at least 32 percent less able to convert beta carotenes to the active forms of vitamin A. Even if you are an effective converter, there are other genes that are involved in how effectively you can absorb and transport the vitamin A in the first place.

How to optimise your vitamin A

Knowing your genetics is a good thing when you can do something about it, and this is a case in point. Setting your absorption ability to one side for the moment, the more variations you have on BCO1, the less you are able to make vitamin A from vegetables, to the point where you may be almost unable to do that conversion at all. In that case, it is important to find other sources of vitamin A, as the nutrient is not only important for eyesight, but also plays several vital roles in your immune system, as well as the condition of your skin and you overall cellular health. Vitamin A is also an important antioxidant that helps your cells to deal with potential causes of inflammation and disease.

You can obtain preformed vitamin A from seafood, liver, eggs, dairy products and meat. If you are vegetarian, then supplementing with a usable form of vitamin A is a good idea, especially if you have the SNPs mentioned above. But how much do you need?

Vitamin A is one of those nutrients that is toxic if you have too much—although you’d need to be eating liver every day over an extended period of time to develop vitamin A toxicity. Hypervitaminosis A, as this is known, may cause adverse effects such as dry skin, hair loss, and, in severe cases, more serious health issues.

Sir John Franklin, the ill-fated Arctic explorer, met a tragic end during his 1845 expedition in search of the Northwest Passage. Stranded in the frigid Arctic, Franklin’s crew faced extreme conditions and looked to the local wildlife, including polar bears (and polar-bear liver), to survive. Unfortunately for them, polar bear liver contains staggeringly high levels of vitamin A, particularly retinol, posing a severe risk of toxicity. This ultimately contributed to the demise of the crew.

Since you are unlikely to be hunting down a polar bear, eating liver as an occasional way to boost your levels is not considered to be a problem, and can be a useful way to boost your vitamin A level, especially with those genetic SNPs. A 100-gram serving of calf’s liver will give you around 6,000 mcg RAE (Retinol Activity Equivalents), so would give you ample to last for several days, as the recommended daily intake is 700 mcg RAE for women or 900 mcg for men. Liver pate can be a better way to eat a smaller amount of liver on a more regular basis. It’s also important to consider the vitamin A content from all dietary sources, including other foods and potential supplements. If you’re consistently exceeding the UL over time, there may be a risk of chronic toxicity.

Exploring and optimising your own genetics

The more I look into genetics and nutrigenomics, the more fascinated I am by it, and the more I realise that we are not at the mercy of our genes. Because of this, I’ve recently incorporated genetic testing as part of my nutrition business. It gives me more scope to provide more powerful solutions for my clients.

BCO1 is one of the core nutrient-related genes that I look at in a nutrigenomics test. It can be a lightbulb moment if you find that you have SNPs that suddenly explain why you’ve suffered for so long with, let’s say, eyesight and skin problems and low immunity. If you are interested in finding out more about how your individual genetic make-up affects how you handle nutrients and whether you have an increased need for certain vitamins and minerals, please get in touch with me (Angela Henderson) using the contact form in the menu at the top of this page, or just book your DNA test direct by ordering the kit from my amazing partner lab here. This test, complete with explanations and guidelines from the partner lab costs £127 and, having looked at a lot of tests and spoken to the companies, I believe it’s one of the most comprehensive on the market. If you tick the box for me to have access to your results, this will give you a free 30-minute consultation with me on one aspect of your health that you would like to focus on. I will email you to discuss this once you have received your results. For full nutrition and lifestyle support and advice and a staged, personalised 12-week plan of action to make full use of the information in your test results, I am always here for you and excited to help you via one of my Nurtural-12 packages.

If you’re looking for new ideas in your quest to increase your vitamin A levels, here’s a tasty liver dish to try. You can serve it with a buttery carrot and swede mash or some fresh egg pasta, and a leafy green salad with olive oil and lemon juice.

Ingredients

- 25g/1oz butter

- 1 large onion, halved and thinly sliced

- 2 tsp balsamic vinegar

- 275-350g/10-12oz calves’ liver, very thinly sliced

- 15g/½oz seasoned cornflour for dusting

- 1 tbsp olive oil

- sea salt

- freshly ground black pepper

- 4 tbsp port or Madeira

- 100ml/3½fl oz fresh beef or chicken stock (you can buy this ready-made in a tub)

- 1 tbsp chopped fresh parsley

- 1 tsbp crème fraïche

Preheat the grill to high. Melt the butter in a large frying pan and fry the onion over a medium heat, stirring frequently, for 7-8 minutes until golden brown.

Season with salt and pepper, add 1 tsp of balsamic vinegar and leave it to bubble up for a few seconds. Remove from the pan and keep warm.

Season the liver on both sides with salt and pepper and then coat lightly in the seasoned flour. Pat off the excess.

Heat the frying pan over a high heat. Add the oil and half the butter and then the slices of liver and cook them over a high heat for 30 seconds on each side, the object being to have the liver nicely browned on the outside, yet still pink and juicy on the inside. Take out of the pan and put it with the onions.

Add the port or Madeira to the pan, bring to the boil and allow to bubble until reduced by half. Add the other tsp of vinegar and cook for a few seconds. Pour in the stock and bring to the boil, stirring. Continue to boil until reduced by half.

Add the fresh parsley, salt and pepper and return the liver and caramelised balsamic onions to the pan. Add the crème fraïche and enjoy!

Let me know in the comments below if you’ve tried and enjoyed this recipe.

Leave A Comment